Surgical Pearls for Pterygium Surgery

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.58931/cect.2025.4156Abstract

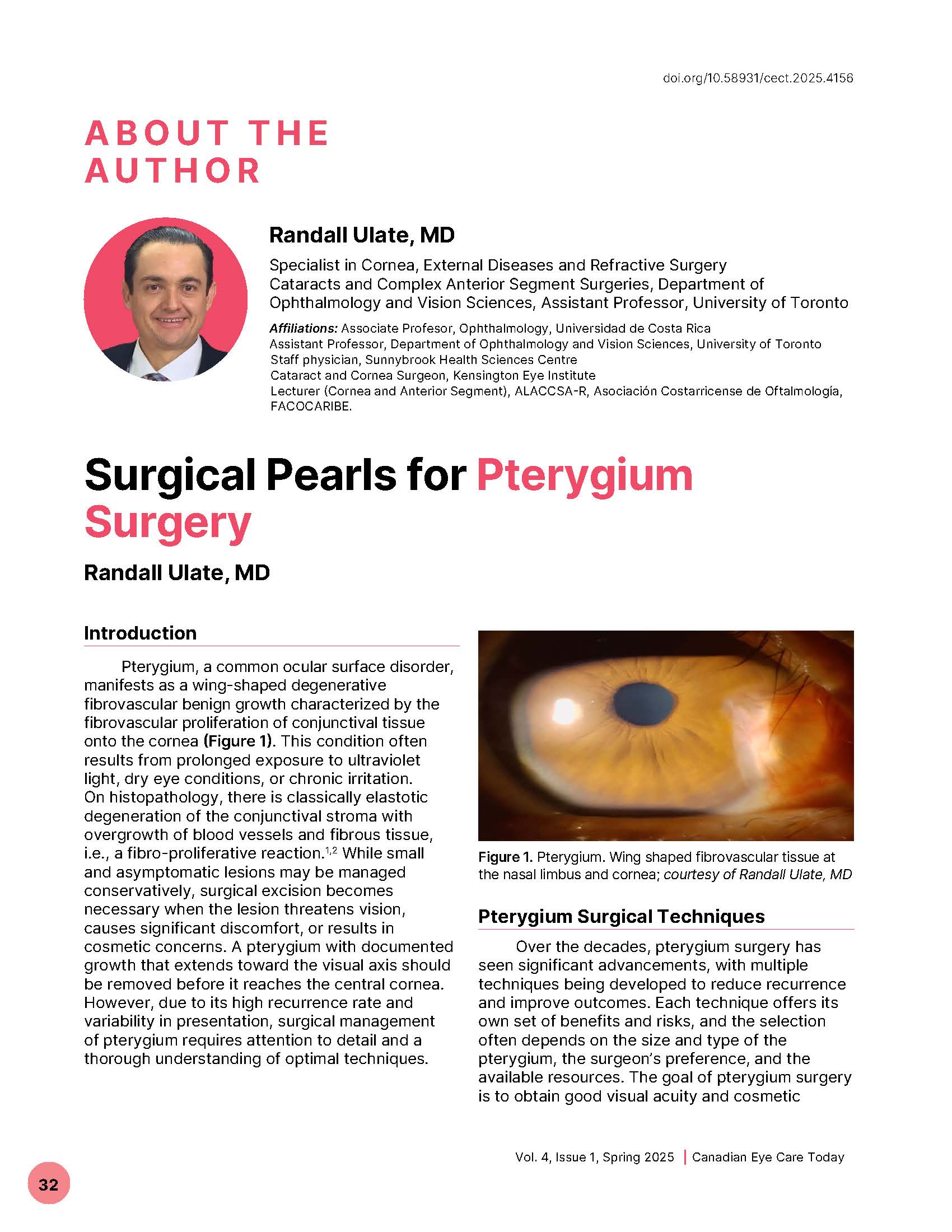

Pterygium, a common ocular surface disorder, manifests as a wing-shaped degenerative fibrovascular benign growth characterized by the fibrovascular proliferation of conjunctival tissue onto the cornea (Figure 1). This condition often results from prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light, dry eye conditions, or chronic irritation. On histopathology, there is classically elastotic degeneration of the conjunctival stroma with overgrowth of blood vessels and fibrous tissue, i.e., a fibro-proliferative reaction. While small and asymptomatic lesions may be managed conservatively, surgical excision becomes necessary when the lesion threatens vision, causes significant discomfort, or results in cosmetic concerns. A pterygium with documented growth that extends toward the visual axis should be removed before it reaches the central cornea. However, due to its high recurrence rate and variability in presentation, surgical management of pterygium requires attention to detail and a thorough understanding of optimal techniques.

References

Dushku N, Reid TW. Immunohistochemical evidence that human pterygia originate from an alteration of the limbal stem cell barrier. Curr Eye Res. 1994;13(7):473–481. doi:10.3109/02713689408999878 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/02713689408999878

Dua HS, Azuara-Blanco A. Limbal stem cells of the corneal epithelium. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;44(5):415–425. doi:10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00109-0 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6257(00)00109-0

Ang LPK, Chua JLL, Tan DTH. Current concepts and techniques in pterygium treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18(4):308–313. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e3281a7ecbb DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0b013e3281a7ecbb

Marcovich AL, Bahar I, Srinivasan S, Slomovic AR. Surgical management of pterygium. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2010;50(3):47–61. doi:10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181e218f7 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/IIO.0b013e3181e218f7

Koranyi G, Seregard S, Kopp ED. Cut and paste: a no suture, small incision approach to pterygium surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(7):911–914. doi:10.1136/bjo.2003.032854 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2003.032854

Rubinfeld RS, Pfister RR, Stein RM, Foster CS, Martin NF, Stoleru S, et al. Serious complications of topical mitomycin C after pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 1992;99(11):1647–1654. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31749-x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(92)31749-X

Donnenfeld ED, Perry HD, Fromer S, Doshe S, Solomon R, Biser S, et al. Combined mitomycin C and conjunctival autograft for primary pterygium: a prospective randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(2):241–248. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00091-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00091-5

Kenyon KR, Wagoner MD, Hettinger ME. Conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(11):1461–1470. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33831-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(85)33831-9

Tan DT, Chee SP, Dear KB, Lim AS. Effect of pterygium morphology on pterygium recurrence in a controlled trial comparing conjunctival autografting with bare sclera excision. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(10):1235–1240. doi:10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160405001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160405001

Hirst LW. The treatment of pterygium. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(2):145–180. doi:10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00463-0 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6257(02)00463-0

Prabhasawat P, Barton K, Burkett G, Tseng SCG. Comparison of conjunctival autografts, amniotic membrane grafts, and primary closure for pterygium excision. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(6):974–985. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30197-3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(97)30197-3

Srinivasan S, Dollin M, McAllum P, Berger Y, Rootman DS, Slomovic AR. Fibrin glue versus sutures for attaching the conjunctival autograft in pterygium surgery: a prospective observer masked clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(2):215–218. doi:10.1136/bjo.2008.145516 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2008.145516

Marticorena J, Rodriguez-Ares MT, Tourino R, Mera P, Valladares MJ, Martines-de-la-Casa JM, et al. Pterygium surgery: conjunctival autograft using fibrin adhesive. Cornea. 2006;25(1):34–36. doi:10.1097/01.ico.0000164780.25914.0a DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ico.0000164780.25914.0a

Shehadeh-Mashor R, Srinivasan S, Boimer C, Lee K, Tomkins O, Slomovic AR. Management of recurrent pterygium with intraoperative mitomycin C and conjunctival autograft with fibrin glue. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(5):730–732. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2011.04.034 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2011.04.034

Martins TG, Costa AL, Alves MR, Chammas R, Schor P. Mitomycin C in pterygium treatment. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(3):465–468. doi:10.18240/ijo.2016.03.25 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2016.03.25

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Canadian Eye Care Today

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.